Ludwig van Beethoven lived between 1770 and 1824. He bridged the gap between the Classical period and the Romantic period Beethoven was born in Bonn, Germany, but lived most of his life in Vienna, Austria.

He studied in Vienna under Mozart and Haydn.

Beethoven was born and brought up in Bonn and first studied harpsichord and violin under the direction of his father, who had dreams of fame and fortune for his young prodigy. Alas, Beethoven was a talent “in waiting” – waiting for the right teacher and the right opportunity. This happened in 1783 with the appointment of Christian Gottlob Neefe to the music staff of the ruling prince, where both Beethoven’s father and grandfather were employed.

In nine years, Beethoven was ready to pursue his studies in Vienna, with Joseph Haydn. He never returned to Bonn. Beethoven had many influential patrons in Vienna and it was clear he was on the verge of becoming a major force in music. In Vienna he first made his reputation as a pianist and teacher, and he became famous quickly.

Four years later, about 1800, after arriving in Vienna, Beethoven started to become deaf. By 1820, when he was almost totally deaf, Beethoven composed his greatest works. These include the last five piano sonatas, the Missa solemnis, and the last five string quartets. He experienced the greatest of despair but accepted his fate with a sense of profound greatness: he would show the world! From this point on, he focused all his energy on his compositions. The first work was his Third Symphony, known as the “Eroica,” a work of infinite levels of expression. Some of Beethoven’s most popular works include the Violin Concerto in D Major, Mass in D Major (“Missa Solemnis”), The Nine Symphonies, including the “Eroica”, “Pastorale” and “Choral”), Egmont Overture, Fidelio, Piano Sonata in C-Sharp Minor (“Moonlight”), Sonata in F Minor “Appassionata”), Piano Concerto No. 5 in E Flat (“Emperor”). Major chamber works include 16 string quartets, 16 piano trios, 10 violin sonatas, and 35 piano sonatas. And what beginning piano student will ever forget “Fër Elise” or many sets of variations, including a set on a theme by Paisiello?

Beethoven waged a constant war with the world he lived in – with his landlords, his debtors, his students, his friends and, of course, his deafness. By the time he wrote his celebrated Fifth Symphony in 1805, he could hear virtually nothing. This symphony has become a musical symbol of victory all over the world.

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony was featured in the Walt Disney movie Fantasia and his Symphony number 5 in the newly released Fantasia 2000.

Beethoven surpassed himself with his Ninth Symphony, finally finished in 1823. He based his main theme of the choral movement on Friedrich von Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”. This theme also became an hymn with the words “Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee. When this symphony was performed in 1824, Beethoven was already deaf and was unaware of the audience applause until he turned around from the conductor’s podium to see the audience.

Beethoven composed 32 piano sonatas, 16 string quartets, 10 overtures, 10 sonatas for violin and piano, 9 symphonies, 5 piano concerti, 5 sonatas for cello and piano, 2 masses, 1 violin concerto, 1 opera and several miscellaneous works.

Beethoven developed a completely original style of music, reflecting his sufferings and joys. His work forms a peak in the development of tonal music and is one of the crucial evolutionary developments in the history of music. Before his time, composers wrote works for religious services, and to entertain people. But people listened to Beethoven’s music for its own sake. As a result, he made music more independent of social, or relgious purposes.

The story is often repeated that when Beethoven died, his last defiant act was to shake his fist at a raging thunderstorm outside. Many have seen this as symbolic of his triumph over deafness, which was a major turning point in his life.

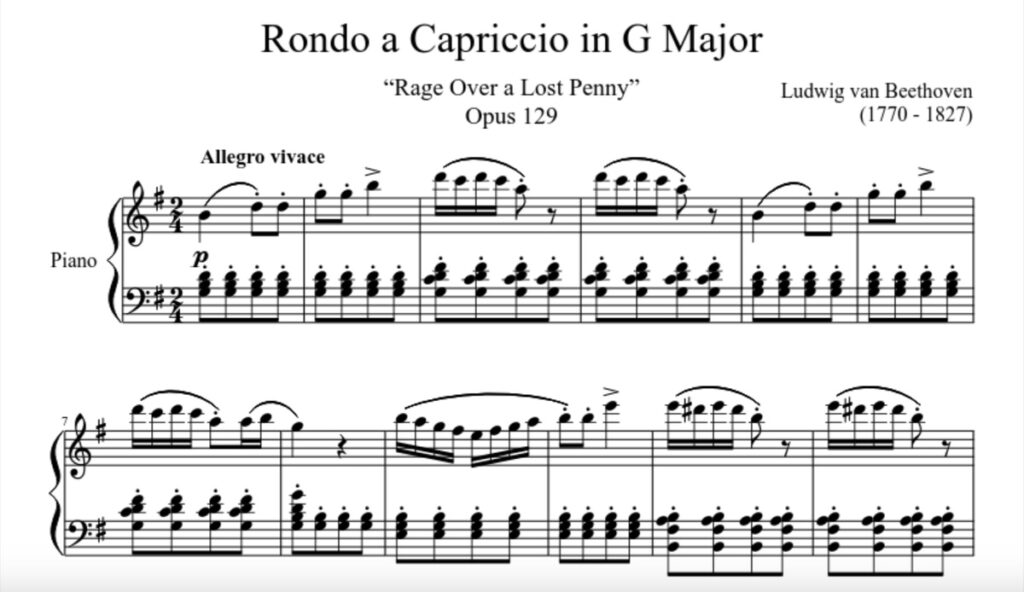

Imagine if Beethoven had known that one day, across the ocean in America, there would be an entire day devoted to lost pennies! Perhaps he would have cheekily timed his vibrant piece, “Rondo alla ingharese quasi un capriccio” (Rondo in the Hungarian [Gypsy] style, like a caprice), Op. 129, to premiere on February 12th, aligning with this quirky observance. This piece, more famously dubbed “Rage Over a Lost Penny,” albeit not by Beethoven himself, dances with a playful irony that might have found a kindred spirit in National Lost Penny Day.

The title “Rage Over a Lost Penny,” though not Beethoven’s own, captures the whimsical fury of the composition, filled with dramatic flourishes and lively tempos that could easily mirror the frustration of losing something as seemingly insignificant as a penny. The piece’s actual title, with its reference to the “Hungarian [Gypsy] style,” contains a little Beethovenian blunder. The word “ingharese” is a bit of a mystery, likely a misspelling on Beethoven’s part of “all’ungharese,” meaning “in the Hungarian style.”

This captivating work is believed to have been penned between 1795 and 1798, during a period when Beethoven was exploring and expanding the boundaries of classical music with his innovative compositions. However, the piece remained unfinished in his lifetime, its full potential only realized when Anton Diabelli, a publisher and composer in his own right, completed and published it in 1828, a year after Beethoven’s passing.

“Rage Over a Lost Penny” stands as a testament to Beethoven’s enduring sense of humor and his ability to infuse even the most light-hearted pieces with depth and complexity. It’s a delightful romp through the scales that invites listeners to imagine Beethoven, not just as a towering figure of classical music, but as a human being capable of playful jests and everyday frustrations.